David Butler Site, Patterson, LA

The Site

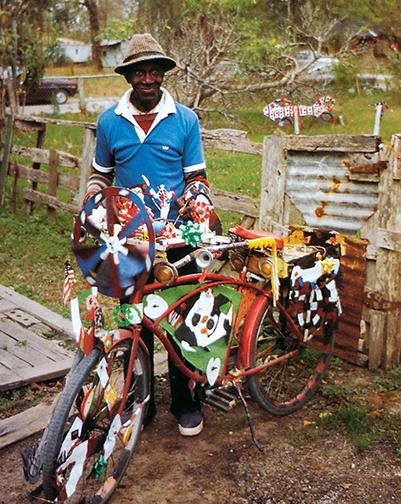

When an injury forced him into retirement, David Butler began animating his home and yard with cut and painted tin animals. Many of the objects that peppered his yard and home were kinetic sculptures, such as whirligigs; stationary pieces, such as a decorated bicycle covered with moving tin pieces; and window shields that took on fanciful silhouettes of animals, people, and imagined creatures. When his wife died in 1968, Butler started constructing “spirit shields,” window coverings and awnings that sheltered his house from both the hot Louisiana sun and, as he believed, unwelcome spirits.

Over the years, Butler’s dynamic home and yard installations have received national attention and acclaim, although Butler’s reaction to this attention was not always positive. Much to his disapproval, a traveling exhibition of his work was curated by William A. Fagaly in 1976; it toured Louisiana from the New Orleans Museum of Art to the Morgan City Municipal Auditorium.

The John Michael Kohler Arts Center has acquired important elements from the Butler environment with the support of Kohler Foundation, Inc.; they include three decorated window coverings from Butler’s home, a whirligig from the yard, and a decorative monkey walking stick as well as his intricately adorned bicycle.

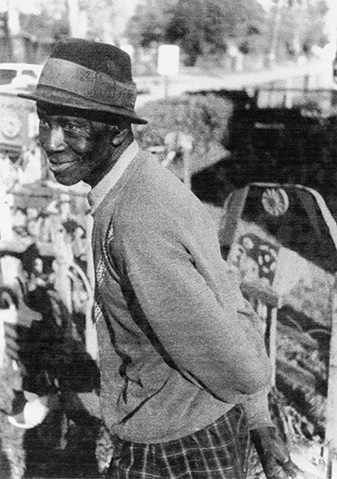

David Butler

1898–1997

David Butler was born in Good Hope, St. Mary Parish, Louisiana, in 1898. His mother was a missionary, and his father was a carpenter. After his mother’s sudden death, Butler dropped out of school in the early 1910s to care for his seven younger siblings while his father continued to work. Butler devoted what little free time he had to drawing whatever he saw, including cane and cotton fields, people at work, shrimp boats, and trains. When his siblings were old enough to care for themselves, he moved to Patterson, Louisiana, to look for work and start a life of his own.

Butler worked a series of jobs such as cutting grass, building roads, loading lumber for shipment on railroad cars, and working a dragline. In 1962, Butler suffered a head injury on the job, was hospitalized for an extended amount time, and was forced to retire due to a permanent disability. With time on his hands, Butler began designing and constructing his domestic space, drawing from the imagery of his dreams and infusing it with his own spiritual beliefs.

Butler never considered himself an artist and didn’t attend any of the exhibitions that happened as his fame and notoriety grew. Collectors and his family members bought and sold pieces from his yard against his wishes and after his death in 1997 the site was completely dismantled.