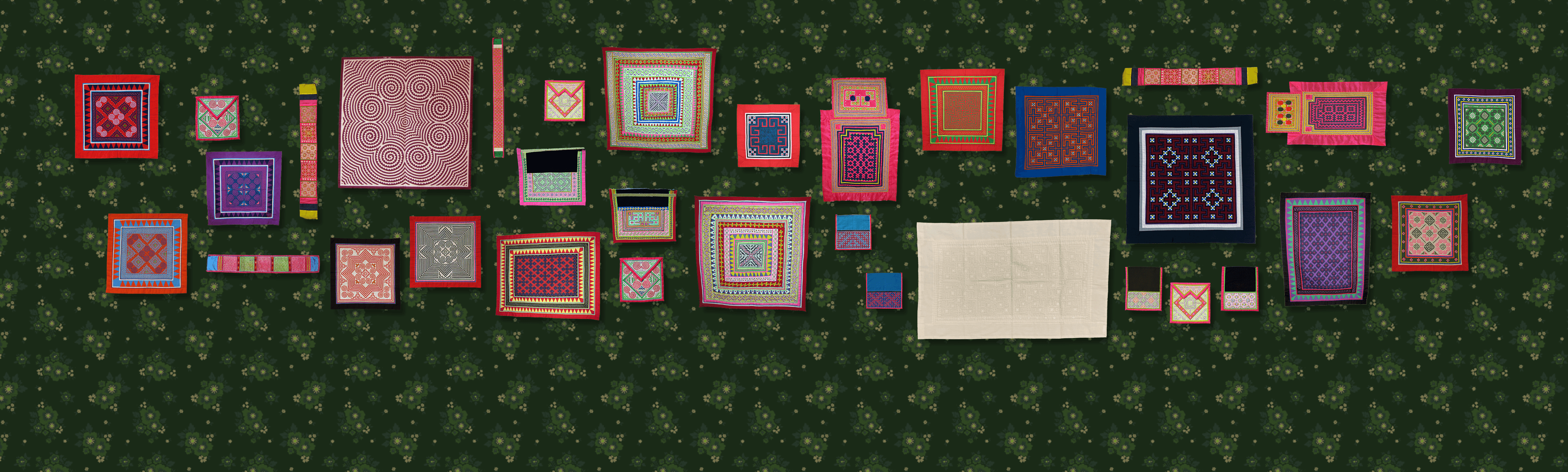

Paj Ntaub “Flower Cloth” Square

A decorative piece, this square textile was made using appliqué and embroidery. It depicts four “cross” shaped “fairy finger’s” motifs that are inverted to denote landscapes covered in “vegetable blossoms.” Made to be commercially sold, these designs are taken from White Hmong dab tshos patterns that are akin to those seen on the Green Mong noob ncoos (funeral pillows).

Xao Yang Lee, untitled, c. 2000–2009; cotton cloth; 29 x 29 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection, gift of Kohler Foundation Inc.

Dab Tsho - Collar Panel

The dab tsho is an embroidered panel attached to the nape of a jacket extending from the collar. It has historically been worn only by girls and women. This dab tsho design is filled with interlocking “house” motifs—a popular paj ntaub (flower cloth) pattern made by HMong Americans who have been physically disconnected from their homelands in Asia.

Sue Yang

Sue Yang’s work was collected when she was sixty-five and living in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. Originally from Xieng Khouang in Laos, she spoke White Hmong. Although her eyesight deteriorated over time due to old age, for over four decades she was renowned for making the finest paj ntaub in her community.

Sue Yang, untitled, 1984; cotton cloth and synthetic cloth; 7 7/8 x 6 1/2 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Paj Ntaub “Flower Cloth” Square

A decorative piece, this square textile was made using appliqué, reverse-appliqué, and embroidery. It uses unconventional fabrics to create a design that experiments with pattern. Motifs such as the “cross”, “eyes”, and “scales,” which usually fill empty background space, are brought to the forefront and emphasized.

Sao Thao

Sao Thao’s work was acquired by the Arts Center while she lived in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, at the age of sixty-four. Originally from Xieng Khouang in Laos, she spoke White Hmong and was married to Youa Vang.

Her grandmother taught her how to embroider at the age of twelve. While many of her items in the collection are characterized by the uncanny use of different fabrics, traditional hemp was central to her practice. From the time she started embroidering to the time she got married at seventeen, she grew, wove, and made eight hemp skirts—a difficult feat to accomplish in five years.

As she aged, her eyesight weakened, which led to more unconventional textile design choices. This adjustment strayed her work from more the traditional and pristine stitches that can be seen in early pieces in the collection.

Sao Thao, untitled, 1984; cotton cloth, cotton, and synthetic cloth; 22 7/8 x 22 5/8 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Paj Ntaub “Flower Cloth” Square

A decorative piece, this square textile was made using appliqué, reverse-appliqué, and embroidery. The threads used to stitch appliqué traditionally appear invisible as they generally come from the plain weave of the cloth being used. This textile, however, is characterized by unusually visible threads and various types of fabrics with intricate weaves. This variety shows how different materials can inspire and require new possibilities for aesthetic experimentation.

Sao Thao

Sao Thao’s work was acquired by the Arts Center while she lived in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, at the age of sixty-four. Originally from Xieng Khouang in Laos, she spoke White Hmong and was married to Youa Vang.

Her grandmother taught her how to embroider at the age of twelve. While many of her items in the collection are characterized by the uncanny use of different fabrics, traditional hemp was central to her practice. From the time she started embroidering to the time she got married at seventeen, she grew, wove, and made eight hemp skirts—a difficult feat to accomplish in five years.

As she aged, her eyesight weakened, which led to more unconventional textile design choices. This adjustment strayed her work from more the traditional and pristine stitches that can be seen in early pieces in the collection.

Sao Thao, untitled, n.d.; cotton cloth, cotton, and synthetic cloth; 23 7/8 x 24 3/4 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Dab Tshos Laus — Funeral Collar Panel

A dab tshos is an embroidered panel attached to the nape of a jacket extending from the collar. The enlarged size of this dab tshos tells us that it is used for funeral rites of the laus (elderly). Unlike a dab tshos that has historically been worn only by girls or women, a dab tshos laus can be worn by anyone regardless of their gender. This piece showcases two prominent poj ntxoog ntiv tes or “fairy’s finger” motifs, which create the illusion of landscape gardens filled with diamond shaped “flowers” and “vegetable blossoms” taken into the afterlife as plots of land for prosperity.

Sao Thao

Sao Thao’s work was acquired by the Arts Center while she lived in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, at the age of sixty-four. Originally from Xieng Khouang in Laos, she spoke White Hmong and was married to Youa Vang.

Her grandmother taught her how to embroider at the age of twelve. While many of her items in the collection are characterized by the uncanny use of different fabrics, traditional hemp was central to her practice. From the time she started embroidering to the time she got married at seventeen, she grew, wove, and made eight hemp skirts—a difficult feat to accomplish in five years.

As she aged, her eyesight weakened, which led to more unconventional textile design choices. This adjustment strayed her work from more the traditional and pristine stitches that can be seen in early pieces in the collection.

Sao Thao, untitled, 1984; 14 1/2 x 17 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Paj Ntaub “Flower Cloth” Square

A decorative piece, this square textile was made using reverse-appliqué, appliqué, and embroidery. Decorative pieces are made to be sold to an outside market. When HMong left Laos at the end of the Secret War, seeking refuge in Thailand, they turned to handicraft entrepreneurship. This piece is signed with text to advertise the artist’s capability and enthusiasm. It reads: “1982. Pa Lee Making Anything Who like call me I can make it.”

Pa Lee

Pa Lee’s work was collected when she was fifty-six and living in St. Paul, Minnesota. Originally from Sayaboury in Laos, she spoke White Hmong and was married to Yong Kia Thao.

Lee’s mother taught her reverse-appliqué when she was only six years old, but she did not learn cross-stitch embroidery until her teenage years. After the end of the Secret War, she and her family sought refuge in Thailand where they lived in Ban Nam Yao refugee camp for five years. There she made large textiles embroidered with inscriptions of loss to grieve the war.

After coming to America in 1980, Lee continued to make textiles to sell. Her pieces in this collection are characterized by border terraces that have “vegetable blossoms” encapsulated inside diamonds.

| Pa Lee, untitled, 1982; cotton cloth, cotton, and synthetic cloth; 16 1/2 x 18 7/8 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection. |

Paj Ntaub “Flower Cloth” Square

A decorative piece, this square textile was made using reverse-appliqué, appliqué, and embroidery. Decorative pieces are made to be sold to an outside market. They have no practical use compared to traditional belts, pockets, and dab tshos (collar panels), which are worn with cultural significance. Instead, decorative pieces rework traditional designs onto square canvases, becoming abstract landscape portraitures to hang on walls. Despite this change in function, the motifs continue to reference homeland, which today inform and maintain HMong identity, culture, and heritage.

Pa Lee

Pa Lee’s work was collected when she was fifty-six and living in St. Paul, Minnesota. Originally from Sayaboury in Laos, she spoke White Hmong and was married to Yong Kia Thao.

Lee’s mother taught her reverse-appliqué when she was only six years old, but she did not learn cross-stitch embroidery until her teenage years. After the end of the Secret War, she and her family sought refuge in Thailand where they lived in Ban Nam Yao refugee camp for five years. There she made large textiles embroidered with inscriptions of loss to grieve the war.

After coming to America in 1980, Lee continued to make textiles to sell. Her pieces in this collection are characterized by border terraces that have “vegetable blossoms” encapsulated inside diamonds.

Pa Lee, untitled, 1985; cotton cloth and synthetic cloth; 16 1/4 x 16 3/8 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Dab Tshos - Collar Panel

The dab tshos is an embroidered panel attached to the nape of a jacket extending from the collar. It has historically been worn only by girls and women. Among some White Hmong people, the dab tsho is decorated with the poj ntxoog ntiv tes or the “fairy’s finger” motif.

The poj ntxoog is a ghost that takes the form of a young girl and lives in the forest. She is often the culprit in mysterious deaths, illnesses, or unfortunate events. Placing the emblem of her ntiv tes or “finger” on the dab tsho acts as a protective charm to scare away any danger or harm in the wild forest.

Lu Lee

When Lu Lee’s work was added to the Arts Center collection, she was age thirty-three and living in St. Paul, Minnesota. Originally from Luang Prabang in Laos, she spoke White Hmong and was married to Yia Cha. Today, she lives in Sacramento, California, with her husband and family.

At an early age, Lee learned how to make the “vegetable blossom” motif from her mother. This involves a skilled technique of both appliqué and embroidery, folding a small fabric cut-out into an even smaller square to be stitched down with intentional lines. Learning this technique at such a young age is what contributes to Lu’s fine needlework, which is characterized by precise designs and uniform stitches.

Today, Lee is an elder artisan who teaches community workshops on traditional HMong embroidery, appliqué, and reverse-appliqué.

Lu Lee, untitled, n.d.; cotton; 8 x 8 1/8 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Dab Tshos - Collar Panel

The dab tshos is an embroidered panel attached to the nape of a jacket extending from the collar. It has historically been worn only by girls and women. Among some White Hmong people, the dab tshos is decorated with tiny appliquéd triangles called ntsais. These dab tshos ntsais triangles represent seeds scattered with “vegetable blossoms” amidst a garden landscape made up of overlapping “fairy’s finger” patterns.

Lu Lee

When Lu Lee’s work was added to the Arts Center collection, she was age thirty-three and living in St. Paul, Minnesota. Originally from Luang Prabang in Laos, she spoke White Hmong and was married to Yia Cha. Today, she lives in Sacramento, California, with her husband and family.

At an early age, Lee learned how to make the “vegetable blossom” motif from her mother. This involves a skilled technique of both appliqué and embroidery, folding a small fabric cut-out into an even smaller square to be stitched down with intentional lines. Learning this technique at such a young age is what contributes to Lu’s fine needlework, which is characterized by precise designs and uniform stitches.

Today, Lee is an elder artisan who teaches community workshops on traditional HMong embroidery, appliqué, and reverse-appliqué.

Lu Lee, untitled, 1984; cotton cloth and synthetic cloth; 7 1/8 x 7 1/8 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Tw Siv — Belt

The tw siv is a decorated belt panel. This style of tw siv is made of five square paj ntaub (flower cloth). Both ends are attached to aprons and/or sashes that are then wrapped and tied around the waist. It keeps jackets, skirts, or pants in place. Made in pairs, this tw siv is one of two that are filled with vibrant flowery images of nature and greenery that chart plots of land.

Xia Xiong

Xia Xiong’s work was collected while she lived in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, and was fifty-four years old. Originally from Xieng Khouang in Laos, she spoke White Hmong and was married to Xia Ying Yang.

Born in 1930 in the city of Long Cheng, Laos, Xiong became an orphan at the age of twelve. Without her mother, she had to learn paj ntaub (flower cloth) through observation. While she made many paj ntaub squares to sell in the marketplace, she always preferred the needlework she put into traditional clothing pieces.

Xia Xiong, untitled, 1975; cotton and synthetic cloth; 3 5/8 x 27 1/8 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Tw Siv — Belt

The tw siv is a decorated belt panel. This style of tw siv is made of five square paj ntaub (flower cloth). Both ends are attached to aprons and/or sashes that are then wrapped and tied around the waist. It keeps jackets, skirts, or pants in place. Made in pairs, this tw siv is one of two that are filled with vibrant flowery images of nature and greenery that chart plots of land.

Xia Xiong

Xia Xiong’s work was collected while she lived in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, and was fifty-four years old. Originally from Xieng Khouang in Laos, she spoke White Hmong and was married to Xia Ying Yang.

Born in 1930 in the city of Long Cheng, Laos, Xiong became an orphan at the age of twelve. Without her mother, she had to learn paj ntaub (flower cloth) through observation. While she made many paj ntaub squares to sell in the marketplace, she always preferred the needlework she put into traditional clothing pieces.

Xia Xiong, untitled, 1975; cotton and synthetic cloth; 3 5/8 x 27 1/8 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Hlab Siv — Belt

The hlab siv is a decorated belt. This style of hlab siv is attached to sashes that help secure it around the waist over jackets, skirts, or pants. It shows intertwining illustrations of vines that look similar to the common spiraling “snail” motif. This is an uncommon design and motif to see among paj ntaub in America.

Blia Lor

Blia Lor’s work was collected when she was sixty-three and living in Madison, Wisconsin. Originally from Xieng Khouang in Laos, she spoke White Hmong and was married to Tong Ge Yang.

She learned paj ntaub (flower cloth) at the young age of five. With a passion for brilliant pinks, greens, and yellows, Lor believes that paj ntaub mastery is determined by the use of these beautiful colors coupled with a large knowledge of making different types of motifs.

Blia Lor, untitled, 1982; synthetic cloth; 2 7/8 x 32 1/2 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Daim Nyias — Baby Carrier

Baby carriers are a testament to HMong textile practices as they are made using all appliqué, reverse-appliqué, embroidery, and batik techniques. They are used by HMong people throughout the diaspora from China to Southeast Asia and the West. This style of baby carrier comes from Laos and America. It depicts a complex garden made of interconnected “crosses” and “spinning hook” motifs surrounded by layers of “terraces” and “mountains”. The top panel is filled with “diamond” shaped flowers and pompons, which serve as watchful eyes to deter any harm from befalling the baby.

| Kang Lee Her, untitled, 1980; cotton cloth and synthetic cloth; 25 1/4 x 15 3/4 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection. |

Paj Ntaub “Flower Cloth” Square

A decorative piece, this square textile was made using reverse-appliqué, appliqué, and embroidery. It centers a “maze” design that is often found on tw siv (belts) worn by the laus (elderly) in funeral rites. “Maze” designs act as a map to help the deceased’s soul navigate the perilous and tricky roads into the afterlife.

| Mao Vue, untitled, 1984; cotton and synthetic cloth; 16 3/8 x 16 3/8 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection. |

Dab Tshos - Collar Panel

The dab tshos is an embroidered panel attached to the nape of a jacket extending from the collar. It has historically been worn only by girls or women. This dab tshos design is decorated with embroidered interlocking “elephant” motifs made from the “double snail” spiral, which represents familial growth and longevity.

Zoua Moua

Zoua Moua’s work was collected while she lived in Appleton, Wisconsin, and was sixty-nine years old. Originally from Xieng Khouang in Laos, she spoke White Hmong and learned how to embroider from her sister at the age of eight. After moving to America in 1980, she made textiles to send as gifts to relatives in Laos and France, lessening the pain of being separated from them.

Zoua Moua, untitled, 1984; synthetic cloth; 7 1/4 x 5 7/8 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Hnab Nyiaj — Money Pockets

The hnab nyiaj is a decorated pocket worn in two ways, as a crossbody or a waist bag. It is usually made in pairs and sometimes worn in fours. This hnab nyiaj is one of two, made using reverse-appliqué, appliqué, and embroidery. It is decorated with “double snail” motifs surrounded by segments of the “house,” which reference the shapes of dragons or mountains offering protection in connection to the earth and home.

Chi Yang

Chi Yang’s work was acquired when she was forty-two years old and living in Fresno, California. Originally from Luang Prabang in Laos, she spoke White Hmong and was married to Chai Pao Xiong. After coming to America in 1979, Yang continued creating traditional costumes for her family and passed on the practice to her daughters.

Chi Yang, untitled, 1984; cotton cloth and synthetic cloth; 7 x 6 3/4 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Paj Ntaub “Flower Cloth” Square

A decorative piece, this square textile was made using reverse-appliqué, appliqué, and embroidery. It features muted tones of black and red suitable for the American marketplace, yet it still integrates subtle pops of traditional vibrant blue and pink to exhibit truer HMong aesthetics. The “house” and “elephant’s foot” motifs are outlined by reverberating lines of mountain terraces to strength and vitality.

Chong Heu

Chong Heu’s work was collected when she was fifty years old and living in Seattle, Washington. Originally from Houayxay in Laos, she spoke White Hmong and was married to Nhia Yia Heu.

When Heu first began making textiles to sell, she used fabrics in her favorite colors derived from traditional HMong clothing. This included vivid pinks, reds, yellows, and greens set against a black backdrop. She recalls a time, however, when an American woman came to her house to show her the actual colors of trees outside. Vivid greens were not true to life and, as such, unfit for American tastes or homes the woman said.

Saddened by this micro aggression, Heu began using more appropriate fabric choices for her market audience but continued integrating bright pops of color into her pieces. No one taught her how to make textiles growing up and she learned from observation. Transcribing these bright traditions into cloth was her way of passing on knowledge to the next generation.

Chong Heu, untitled, 1984; cotton cloth and synthetic cloth; 15 1/2 x 15 1/2 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Paj Ntaub “Flower Cloth” Square

A decorative piece, this square textile was made using reverse-appliqué, appliqué, and embroidery. It centers the “house” and “elephant’s foot” motifs, which are symbolic of family and home rooted in the homelands of Asia. For HMong-Americans, homeland is specifically linked to the country of Laos, which is known as the land of a million elephants. Among HMong in Vietnam, however, these combined motifs represent family in the form of four individuals holding hands around a hearth.

Chong Heu

Chong Heu’s work was collected when she was fifty years old and living in Seattle, Washington. Originally from Houayxay in Laos, she spoke White Hmong and was married to Nhia Yia Heu.

When Heu first began making textiles to sell, she used fabrics in her favorite colors derived from traditional HMong clothing. This included vivid pinks, reds, yellows, and greens set against a black backdrop. She recalls a time, however, when an American woman came to her house to show her the actual colors of trees outside. Vivid greens were not true to life and, as such, unfit for American tastes or homes the woman said.

Saddened by this micro aggression, Heu began using more appropriate fabric choices for her market audience but continued integrating bright pops of color into her pieces. No one taught her how to make textiles growing up and she learned from observation. Transcribing these bright traditions into cloth was her way of passing on knowledge to the next generation.

Chong Heu, untitled, 1984; cotton cloth and synthetic cloth; 15 1/4 x 15 5/8 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Hlab Siv — Belt

The hlab siv is a decorated belt. This style of hlab siv, worn by White Hmong, are made of five alternating square paj ntaub (flower cloth) panels. The ends are attached to aprons and/or sashes to be tied around the waist, keeping jackets, skirts, or pants in place. Generally made in pairs, this hlab siv does not have a partner in the collection. Its design is indicative of “landscape” and “maze” motifs used in funerary rites for the laus (elderly) to take as plots of land with them into the afterlife.

Hnab Nyiaj - Money Pockets

The hnab nyiaj is a decorated pocket worn in two ways as a crossbody or a waist bag. It is usually made in pairs and sometimes worn in fours. This hnab nyiaj is one of two, made using reverse-appliqué, appliqué, and embroidery. It is decorated with full and segmented “house” motifs, referencing the shapes of dragons or mountains, which offer protection and connection to the earth and home.

Lao Thor, untitled, 1984; cotton cloth and synthetic cloth; 6 3/4 x 6 3/4 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Paj Ntaub “Flower Cloth” Square

A decorative piece, this square textile was made using reverse-appliqué, appliqué, and embroidery. Made for the American marketplace, it preserves the vibrant and tantalizing color combinations of traditional HMong aesthetics.

Mee Moua

Mee Moua was forty-three and living in San Diego, California, when her work was acquired by the Arts Center. Originally from Sam Neua in Laos, she spoke Green Mong and was married to Thai Her.

She learned needlework from her mother at the age of eight. Although many of her designs modify and enlarge traditional patterns, they show a conscious effort to preserve the vibrant color combinations of HMong aesthetics even within the American marketplace.

Mee Moua, untitled, 1983; cotton cloth, cotton, and synthetic cloth; 16 3/4 x 16 1/2 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Paj Ntaub “Flower Cloth” Square

A decorative piece, this square textile was made using reverse-appliqué, appliqué, and embroidery. “Double snail” and “house” motifs are enveloped in “mountain” terraces that embody the protective spirit of dragons.

Mee Moua

Mee Moua was forty-three and living in San Diego, California, when her work was acquired by the Arts Center. Originally from Sam Neua in Laos, she spoke Green Mong and was married to Thai Her.

She learned needlework from her mother at the age of eight. Although many of her designs modify and enlarge traditional patterns, they show a conscious effort to preserve the vibrant color combinations of HMong aesthetics even within the American marketplace.

Mee Moua, untitled, 1984; cotton cloth, cotton, and synthetic cloth; 17 1/2 x 17 3/8 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Paj Ntaub “Flower Cloth” Square

A decorative piece, this square textile was made using reverse-appliqué, appliqué, and embroidery. “Heart” motifs derived from the “double snail” showcase a design alteration that better communicates the symbolic meaning of family and love to an American marketplace and audience.

Mee Moua

Mee Moua was forty-three and living in San Diego, California, when her work was acquired by the Arts Center. Originally from Sam Neua in Laos, she spoke Green Mong and was married to Thai Her.

She learned needlework from her mother at the age of eight. Although many of her designs modify and enlarge traditional patterns, they show a conscious effort to preserve the vibrant color combinations of HMong aesthetics even within the American marketplace.

Mee Moua, untitled, 1984; cotton cloth, cotton, and synthetic cloth; 17 1/8 x 17 1/4 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Paj Ntaub “Flower Cloth” Square

A decorative piece, this square textile was made using batik and appliqué. The indigo blue batik illustrations center a “hook” motif enveloped in “crosses.” These illustrations are appliquéd with geometric “double snail” motifs, indicative of the “elephant’s foot.”

Cho Vang

Cho Vang’s work was collected when she was fifty-eight and living in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Originally from Sayaboury in Laos, she spoke Green Mong and was married to Youa Pao Xiong.

Vang was one of the few HMong women who continued the practice of batik after moving to America. In the states there was less demand for traditional clothing items, which decreased the need for batik fabrics. Indigo plants were also hard to come by and with tightening customs inspections, having them sent over by relatives was not an easy task. The scarcity of materials and lack of demand are reasons why the practice dwindled early on in HMong migration to the U.S.

| Cho Vang, untitled, 1983; cotton cloth, cotton, and synthetic cloth; 13 1/8 x 12 7/8 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection. |

Paj Ntaub “Flower Cloth” Square

A decorative piece, this square textile was made using reverse-appliqué. It depicts “double snail” motifs indicative of the “elephant’s foot,” with “mountain terraces” reverberating from its outlines. These motifs include jagged shapes of “dragon” scales representing power, prestige, and protection.

Cher Lee

Cher Lee’s work was collected while she lived in Fresno, California, and was thirty-three years old. Originally from Luang Prabang in Laos, she spoke White Hmong and was married to Shoua Cha. In her paj ntaub (flower cloth), she likes to use nontraditional colors of various shades to create decorative hangings for sale.

Cher Lee, untitled, 1984; cotton and synthetic cloth; 30 3/8 x 30 5/8 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Paj Ntaub “Flower Cloth”

A decorative piece, this rectangular textile was made using appliqué and embroidery. It features appliquéd “hook” motifs illustrating landscapes outlined by line stitches resembling the “house” motif. Its borders include the “fence” motif that emphasizes protection alongside the “mountains.” It is similar to another piece in the collection made by May Yang.

Pang Vang, untitled, n.d.; 26 1/2 x 20 1/4 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Paj Ntaub “Flower Cloth”

A decorative piece, this rectangular textile was made using appliqué and embroidery. It features appliquéd “hook” motifs illustrating landscapes outlined by line stitches resembling the “house” motif. Its borders include the “fence” motif that emphasizes protection alongside the double layers of “mountains.” It is similar to another piece in the collection made by Pang Vang.

May Yang

May Yang lived in Fresno, California, and was age thirty-seven when her work was acquired by the Arts Center. Originally from Xieng Khouang in Laos, she spoke Green Mong and was married to Wang Xang Vang. Yang came to America in 1979.

May Yang, untitled, c. 1984; cotton cloth; 29 3/4 x 23 7/8 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Daim Nyias — Baby Carrier

Baby carriers are a testament to HMong textile practices, made of appliqué, reverse-appliqué, embroidery, and batik. They are used by HMong people throughout the diaspora from China to Southeast Asia and the West. This baby carrier depicts terraces and mountains surrounding a complex garden made of “hook” motifs alluding to the legendary kingdom of the HMong’s original homelands in China.

May Vang, untitled, 1984; cotton cloth, cotton, and synthetic cloth; 23 x 15 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Hnab Nyiaj — Money Pockets

The hnab nyiaj is a decorated pocket worn in two ways, as a crossbody or a waist bag. It is usually made in pairs and sometimes worn in fours. This hnab nyiaj is one of two, made using reverse-appliqué, appliqué, and embroidery. It is decorated with “double snail” motifs surrounded by segments of the “house,” which reference the shapes of dragons or mountains offering protection in connection to the earth and home.

Chi Yang

Chi Yang’s work was acquired when she was forty-two years old and living in Fresno, California. Originally from Luang Prabang in Laos, she spoke White Hmong and was married to Chai Pao Xiong. After coming to America in 1979, Yang continued creating traditional costumes for her family and passed on the practice to her daughters.

Chi Yang, untitled, 1984; cotton cloth and synthetic cloth; 7 x 6 3/4 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Hlab Siv — Belt

The hlab siv is a decorated belt. This style of hlab siv, worn by White Hmong, are made of five alternating square paj ntaub (flower cloth) panels. The ends are attached to aprons and/or sashes to be tied around the waist, keeping jackets, skirts, or pants in place. Generally made in pairs, this hlab siv does not have a partner in the collection. Its design is indicative of “landscape” and “maze” motifs used in funerary rites for the laus (elderly) to take as plots of land with them into the afterlife.

Artist unknown, untitled, n.d.; cotton cloth and synthetic cloth; 3 1/2 x 22 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection, gift of Natalie Vue.

Paj Ntaub “Flower Cloth” Square

A decorative piece, this square textile was made using appliqué and embroidery. It depicts four “cross” shaped “fairy finger’s” motifs that denote “landscapes” covered in “vegetable blossoms.” Made to be commercially sold, these designs are taken from White Hmong dab tshos patterns that are akin to those seen on the Green Mong noob ncoos (funeral pillows).

Xao Yang Lee

Xao Yang Lee’s work was collected when she was thirty-eight and living in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. Originally from Xieng Khouang in Laos, she spoke White Hmong and lived in Long Cheng during the Secret War. Her first husband, Chia Vang Lee, was a soldier in the war who did not return. When she moved to Sheboygan in 1981, she remarried Tou Moua Lee.

Lee began making needlework at the age of five. Although their family was White Hmong, her mother learned how to make Green Mong paj ntaub and batik, which she passed onto Lee.

In the Thailand refugee camps, Lee took to needle and thread as an economic means to support her children as a single mother. Against all odds, she has made a name for her handiwork throughout Wisconsin, having had her work featured in numerous Art Center exhibitions.

Xao Yang Lee, untitled, c. 2000–2009; cotton cloth; 21 x 20 1/2 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection, gift of Kohler Foundation Inc.

Hnab Nyiaj - Money Pockets

The hnab nyiaj is a decorated pocket worn in two ways as a crossbody or a waist bag. It is usually made in pairs and sometimes worn in fours. This hnab nyiaj is one of two, made using reverse-appliqué, appliqué, and embroidery. It is decorated with full and segmented “house” motifs, referencing the shapes of dragons or mountains, which offer protection and connection to the earth and home.

Lao Thor, untitled, 1984; cotton cloth and synthetic cloth; 6 3/4 x 6 3/4 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection.

Paj Ntaub “Flower Cloth” Blanket

A decorative piece, this large textile was made using appliqué and embroidery. It depicts eight enlarged “cross” shaped “fairy finger’s” motifs that denote landscapes covered in “vegetable blossoms.” Made to be commercially sold, these designs are taken from White Hmong dab tshos patterns that are akin to those seen on the Green Mong noob ncoos (funeral pillows). Today, large textiles like these are used as funeral blankets for the deceased.

Xao Yang Lee

Xao Yang Lee’s work was collected when she was thirty-eight and living in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. Originally from Xiangkhouang in Laos, she spoke White Hmong and lived in Long Cheng during the Secret War. Her first husband, Chia Vang Lee, was a soldier in the war who did not return. When she moved to Sheboygan in 1981, she remarried Chia Vang Lee.

Lee began making needlework at the age of five. Although their family was White Hmong, her mother learned how to make Green Mong paj ntaub and batik, which she passed on to Lee.

In the Thailand refugee camps, Lee took to needle and thread as an economic means to support her children as a single mother. Against all odds, she has made a name for her handiwork throughout Wisconsin, having had her work featured in numerous Art Center exhibitions.

Xao Yang Lee, untitled, c. 2000–2009; cotton cloth; 42 3/4 x 26 1/2 in. John Michael Kohler Arts Center Collection, gift of Kohler Foundation Inc.

ab Tshos Laus — Funeral Collar Panel

A dab tshos is a decorated panel attached to the nape of a jacket extending from the collar. The enlarged size of this dab tshos tells us that it is used for funeral rites of the laus (elderly). It displays appliquéd motifs of “home” that evoke a longing and hope for familiarity.

Sao Thao

Sao Thao’s work was acquired by the Arts Center while she lived in Sheboygan, Wisconsin, at the age of sixty-four. Originally from Xieng Khouang in Laos, she spoke White Hmong and was married to Youa Vang.

Her grandmother taught her how to embroider at the age of twelve. While many of her items in the collection are characterized by the uncanny use of different fabrics, traditional hemp was central to her practice. From the time she started embroidering to the time she got married at seventeen, she grew, wove, and made eight hemp skirts—a difficult feat to accomplish in five years.

As she aged, her eyesight weakened, which led to more unconventional textile design choices. This adjustment strayed her work from more the traditional and pristine stitches that can be seen in early pieces in the collection.